October 1, 2018 – By Monday, all of the 16- and 17-year-olds currently detained on Rikers Island are set to be moved to the Horizon Juvenile Facility, a secure detention center designed for juveniles in the Bronx.

It’s a big step and a pillar of the implementation of the state’s Raise the Age Law, which makes New York a state where juveniles are not treated as adults in the criminal justice system and brings it into line with every other state in the country besides North Carolina. Today is the deadline the state set for the move.

“We are on the cusp of one of the most far-reaching and progressive juvenile justice reforms in decades,” said David Hansell, commissioner for the city’s Administration for Children’s Services, which oversees the juvenile justice system, at a recent press conference highlighting some of the changes.

It is a milestone the city wants to celebrate. At a recent press event this August, reporters, including City Limits, toured the city’s other juvenile detention center, the Crossroads Juvenile Facility in Brownsville, where all of the youth in ACS secure detention are currently held. ACS and facility officials showed off renovations and touted the facility’s programming and services for inmates.

The teenagers leaving Rikers Island are heading to a facility that looks much like the Crossroads facility—it was built at the same time with the largely the same design. Horizon is currently undergoing renovations to have the same renovated courtyard and interior spaces as Crossroads. By many measures, that is a positive thing: By departing Rikers they will leave a facility with a deep culture of violence and abuse, which is part of one of the most notoriously awful jail complexes in the country, and enter a facility that was designed with youth in mind. In addition to simply being in a location where their families and loved ones can visit them more easily, they will have access to mental health services, music and arts programming from community organizations, Department of Education classes and a renovated outdoor recreational space.

But it’s still a jail. It’s ringed with barbed wire. To enter, you must buzz in through two steel doors. These 16- and 17-year-olds are, in some ways, merely moving from one secure detention facility to another. And like Rikers, the facility they’re moving to has its own history of abuse and violence.

Reforms and violence

At Crossroads, officials showed off a renovated living unit where adolescents in custody sleep. It’s a set of 10-or-so bedrooms that open on to a central space containing specially designed chairs, a table with connected stools that was bolted to the floor and a wall-mounted TV encased in plexiglass.

Among the renovations officials touted were hardened walls and doors and a system that allows youth to push a button to be granted access to leave their sleeping cells. They also noted a new colorful paint job on the cinder-block walls.

“We don’t want this environment to ever look like a jail or a penitentiary,” said Louis Watts, the facility’s executive director, as he showed reporters around and explained his goal of building trusting relationships with the inmates.

There’s no mistaking this facility for a school or a warm environment, however, especially when it comes to the city’s published data.

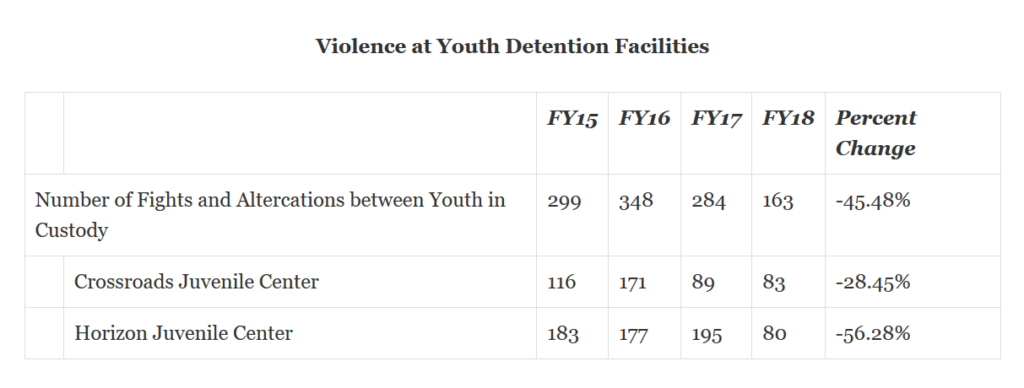

The number of serious incidents in ACS secure detention facilities have fallen significantly in the past several years, but still remain high. In the 2018 fiscal year, there were 163 fights between youth in custody and 385 instances when officials used mechanical or physical restraints. Eighty-six of the fights and 29 of the restraining instances resulted in an injury to an inmate. There were 1,750 inmates admitted to these facilities during that period and the average daily population was 85 youth per day.

At Rikers Island, the numbers look worse. There were 966 16- and 17-year-olds admitted in the same period and 497 fights according to Jason Kerston, a press officer for the Department of Corrections (DOC). In addition, there were 58 assaults in which adolescents were involved and 478 uses of force by DOC officers on adolescent inmates.

At Rikers Island, the numbers look worse. There were 966 16- and 17-year-olds admitted in the same period and 497 fights according to Jason Kerston, a press officer for the Department of Corrections (DOC). In addition, there were 58 assaults in which adolescents were involved and 478 uses of force by DOC officers on adolescent inmates.

These details fit the common narrative about these facilities— that they’re full of violence and abuse: Last August and this May, two former inmates filed separate suits in federal court alleging that a guard at the Horizon facility sexually assaulted them. One complainant also said that “he was repeatedly punched by Horizon staff and discouraged from seeking medical attention at the center’s clinic” and that staff at Horizon smuggled in alcohol and drugs to reward complicity. Both suits are still pending.

“There’s just never been such thing as a good juvenile detention facility—it’s never been demonstrated,” said Ruben Austria, a juvenile justice advocate the executive director of Community Connections for Youth, an organization that offers reentry and alternative to detention programs for juvenile offenders in the South Bronx.

“So why do we keep on replicating failure? You’re worried about kids being violent, you’re kind of ensuring that they’ll be violent when they’re in there,” he said.

Austria is one of a handful of voices quietly advocating for abolition of juvenile detention in NYC all together.

It’s a logical next step for a system that has undergone significant reform in the past decade but not a call that has been taken up broadly. Implementing Raise the Age and reforming the juvenile detention system as it is has been the biggest priority

Youth currently in the city’s juvenile detention system are under 16 and were sent there after an arrest either by court order or at the discretion of the Police Department, or as part of the disposition of their case after a hearing. Youth currently held at Rikers Island were arrested when they were between 16 and 17 years old and, because of state law, automatically treated as adults in the judicial system. Mostly, they are awaiting trial.

The number of juvenile inmates in city juvenile detention facilities has dropped significantly. In 1999, 5,300 youth under 16 were admitted to secure detention in New York City. In 2017, it was 1,754. Mostly, this mirrors a falling arrest and crime rate. The number of juvenile arrests has fallen 67 percent since 2010, from 12,744 to 4,099 in 2017. But it’s also the result of diversion programs like Austria’s that send youth facing certain charges to supportive, community-based programs that address needs in the children’s lives and connect them to neighborhood-based support systems like sports coaches, mentors and local organizations.

Because many youth are often not held in detention for long (In the 2018 fiscal year, the average length of stay in the city’s secure and non-secure juvenile detention facilities was 19 days), at one point this August, there were just 37 inmates held in ACS custody. As many as 97 more could be coming with the transfer of the 16 and 17 year old’s from Rikers Island, according to the DOC.

“What you’ve seen is that the justice system has more than shrunk in half,” Austria said. “Its down in all these categories, from arrests, to court filings to placements.”

Austria’s connection to the juvenile justice system goes back almost two decades as a community advocate and organizer. He was involved in the 2012 Close to Home campaign which led to numerous upstate youth prison closures and transferred custody of convicted youth from the state to the city.

According to Felipe Franco, deputy commissioner of ACS who oversees the city’s juvenile justice system, the smaller populations in the facilities mean that there are more resources available to devote for support of inmates and staff alike.

For example, that means resources to support mental-health coverage and programs for youth. The crossroads facility has on-site clinical psychologists via a partnership with NYU-Langone and Bellevue Hospitals.

It also means creating staff schedules so that employees working with inmates develop relationships with them and with each other. In each living unit, there are youth development specialists, a case manager, a social worker and physician.

“Those people consistently work together. They consistently meet, they consistently know each other well, and they constantly talk about the young people that are under their care,” said Franco. “So the young person, in a way, has the predictability of knowing that tomorrow, when I wake up and may not be in a good mood, the person that’s going to be making me brush my teeth is going to be the same person that does that every day.”

“That has been an essential piece of what we have implemented over the last five years,” he said.

Franco says the other biggest change he’s overseen is bringing community organizations into the facilities to provide programming instead of running it through ACS.

He mentioned a partnership with Carnegie Hall—some youth got to perform there—and with a program called Cure Violence, which seeks to stem youth violence by treating it like an infectious disease. This summer, the Freedom School, a program of the Children’s Defense Fund, operated a literacy program in Crossroads.

According to Franco, these programs are an extension of the reform efforts that go back over the past 20 years and which began with an effort to close the Spofford Youth Detention Center in Hunts Point in 1998.

“You have to give a lot of credit to the advocates. To the system leaders who have banded together and have said we realize that the system is very harmful and we have to keep our kids out of it,” said Austria. “And you have to give a lot of credit to the network of community programs that have stepped up to work with young people in diversion. And in alternatives to detention.”

Despite these efforts, the system continues to face a number of persistent problems. Incidents and altercations between youth and staff as well as youth complaints of abuse remain constants. Also unchanging is a stream of youth that appear to keep ending up back in the system. Each of these metrics has stayed steady or climbed, even with the declining population in secure detention.

For example, in 2010, the percentage of youth admitted to detention who had been previously admitted to detention was 53 percent. In 2018 it was 58 percent.

One explanation for these persistent metrics is that as the number of youth going into secure detention has contracted, the population that remains in secure detention is one that is somehow more prone to violence—an argument used to justify detention.

But the re-admission rate is also a powerful indictment of the system. It suggests the majority of the population the detention system is serving is one that is stuck within the system. That’s a major reason why Austria and others want to end juvenile detention. They understand that youth crime and violence are often a product of trauma and that even a night in a detention facility only causes more.

A different approach?

Shaena Fazal is the National Director for Public Policy and Youth Advocate Programs, an organization that coordinates community-based alternatives to incarceration and advocates for policy.

“Any one of us would feel traumatized from a night in a detention facility,” she says. “You’re in a locked facility, it’s not clear when you’re going to be free. You don’t have access to information…You’re separated from your family.”

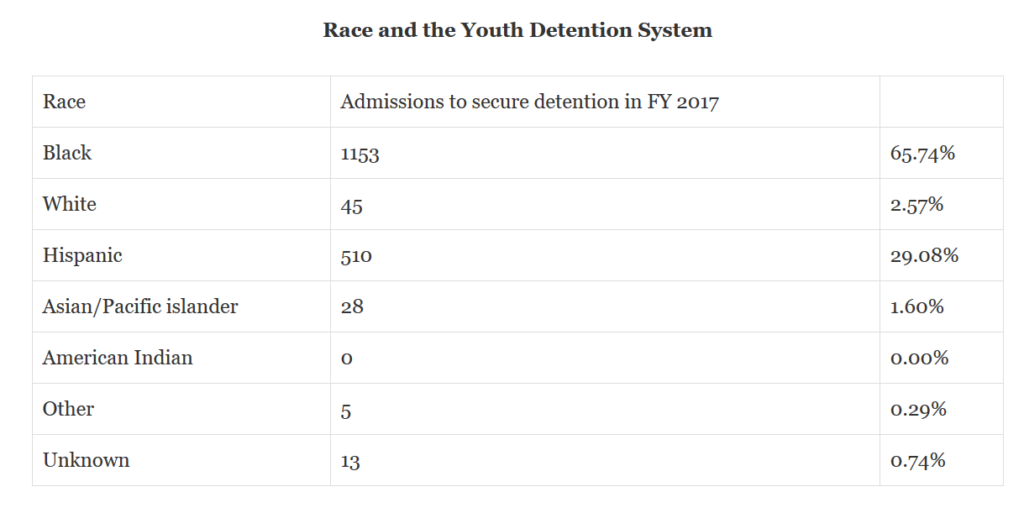

Fazal, Austria and others are also advocating for an end to juvenile incarceration because they know that youth crime is concentrated in specific poor and minority communities which have suffered from decades of disinvestment and discrimination. They believe that building community capacity and connecting youth to supportive services in their communities is the best way to succeed.

Describing the typical adolescent in the juvenile system, Vidal Guzman, a community organizer with Just Leadership USA, emphasized this point.

Describing the typical adolescent in the juvenile system, Vidal Guzman, a community organizer with Just Leadership USA, emphasized this point.

“The solution is investing in the communities that he’s living in. Investing in the things that help him out to be him. Investing in more reentry, more affordable housing, drug and alcohol treatment for families.”

Guzman was sent to Rikers Island at 16 years old, and, after going through a community re-entry program and an employment program for former inmates, got involved with criminal justice organizing. He says violence is a product of broken communities and systemic inequality.

At this juncture, however, momentum doesn’t seem to be in the favor of the community approach. As the city prepares to move youth off of Rikers, it has invested approximately $300 million in renovating these facilities and reform-minded advocates say that once constructed, jails demand to be used.

The facilities each have a capacity of around 150 beds. And adding merit to the argument made by reformers, the Horizon facility will be staffed with officers from the Department of Correction who previously worked on Rikers Island, rather than ACS staff who specialize in working with children. The city wants to phase these DOC workers out within two years but cannot hire and train enough ACS workers fast enough. It also says the DOC workers will foster continuity for the teenagers.

There will always be a place for secure youth detention, says Franco. “At the end of the day, we only get those kids who are meant to be in detention, and the majority of kids who are arrested have been released on their own or by the court or department of probation.”

Franco suggests this is because there will always be a small handful of youth who are so violent that they are a risk to their communities and themselves: keeping them in a controlled environment mitigates this risk.

Some reformers, however, say otherwise. Mishi Faruque is the national field director at Youth First, an organization that has led campaigns in numerous states to shut down youth correctional facilities and has herself been involved in reforming the youth justice system in New York for many years. She cites evidence that suggests incarceration is so damaging that it actually makes youth far less likely to complete high school and more likely to be incarcerated as an adult following their release. The percentage of former offenders in the system is a strong piece of evidence for this argument.

“All of the evidence proves that incarceration does not work. Locking up young people fails to protect public safety,” says Faruque.

Article originally ran on City Limits.